In episode 11 of the Art and Science of Running Podcast we visit with Tommy Rivers Puzey. Tommy is a husband, father, accomplished marathoner, trail and ultra runner, iFit Trainer, anthropologist, linguist, doctor of physical therapy and licensed massage therapist who works on some of the best endurance athletes in the world when they are training in his hometown of Flagstaff, Arizona.

What motivates Tommy to get out the door and run?

“Trying to keep my own mental and physical health in check. Movement outside helps me keep my own emotional health.”

“The first biggest motivator is to get my head on straight before the rest of the day starts.”

“There are few people whose company I enjoy as much as the voices in my own head.”

“More than anything, I’m motivated by fear of not reaching my potential.”

What was it like growing up in the Puzey home?

“We always knew that we were loved, but there was always an expectation to excel.”

What motivated Tommy to pursue the academic tracks that he pursued?

“Our dad taught us from a young age that you can either work with your hands or you can work with your mind. If you choose to work with your mind, you have to go to college and if you want to go to college I’m not going to pay for it so you either have to be a scholar or an athlete or both.”

“We knew that if we wanted to work with our minds that we needed to go to college so we tried to become the best students and athletes that we could be so that we could pay for college.”

“Waste of any kind is sinful. Waste of food, waste of time, waste of opportunity. Waste of potential is the very worst form of waste.”

“Anthropology class felt like Sunday dinner with our family. It just felt like home being in the anthropology department and that’s what Jake was studying so that’s what I did.”

When did athletics come into the picture?

“Our recreation as kids was simply being outside in the rural southwest.”

“You learn to run as kids and then you are told to stop and then eventually listen. Whether it’s for church, or school, or the pool. We learned to run as kids and we just never stopped.”

Tommy has had success on the trails and the roads. Some find the transition back and forth difficult.

How does he specifically target specific types of running races?

“I start my weeks from the back to the front. . . People have these preconceived notions that you are either a trail runner or a road runner. One of the first things I learned about when I first started studying human physiology is Wolff’s Law. Wolff’s Law essentially says that bones will strengthen themselves. The fibres of the bones will align themselves specifically in response to the stresses that are placed upon them. If you stress a tissue or blood or tendon a little bit those tissues will make adaptations and become what they are being trained to become. If you stress it too much without adequate recovery you will get injured.”

Tommy’ weekly training schedule:

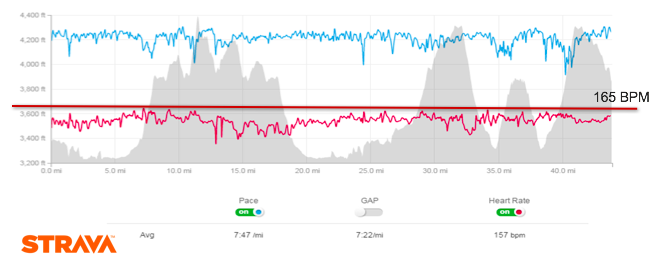

- Five days a week Tommy does what he calls the Vuelta del Taco Run which is 10 miles from his home on a dirt mountain road to Del Taco where he eats a burrito and drinks a Powerade and then he returns home (10 miles) on the same mountain run. These 20 mile runs are done below the first ventilatory threshold at a heart rate of about 140 BPM. The last mile or two of the runs, Tommy inserts 4-6 x 30 second strides.

“Other than that, I do strides. I define strides as pretending that I’m starting a 10K race 4-6 times in the last mile of my run.”

- Hard, race specific work with a group – either on the road or the track.

“I feel like I need to do really hard, specific work on the track or the road to keep the turnover going up and working the neurology.”

- Day in the Canyon – 5,000 ft down and 5,000 ft up – usually to the River or Phantom Ranch and back up.

“If I maintain the durability that comes from running in the [Grand] Canyon once a week, I can handle better the impact that comes on my legs if I’m racing hard on any kind of course.”

“I try to find a way to make training a part of my everyday life. Figure out ways to make training not be something that you dread and something that you enjoy.”

“If I do it that way, there is always going to be stress, but emotional stress isn’t going to be one of the stresses. If there is not emotional stress contributing to that total pool of stress from my training – if it’s not something that I dread. If I’m not worried about hitting a certain pace or heart rate zone then my total overall level of stress is lower which means my cortisol levels are lower and my testosterone is higher and then my mood is better and my energy is greater. All of the things that people are illegally doing to try gain an advantage. You can get all of those same advantages by changing your perspective and mindset of what you’re doing.“

“I learned that from run commuting during graduate school. I was running 24 miles a day to and from school. It never felt like I was training because it was simply my mode of transportation to and from school.”

“If you cannot injure yourself during a marathon, you’re the fittest you’ve ever been three weeks after the marathon. Your body can absorb the fitness, the durability, the neuromuscular efficiency from that marathon the same way that it can from any training run.”

Tommy recommends the book, 80/20 Running by Matt Fitzgerald as a foundation upon which training should be designed: “80% percent of training should be under your first ventilatory threshold. What’s important is that the other 20% needs to be at a high intensity. If you’re running 100 miles a week that means that you can do 20 miles of quality work. The problem is that people don’t do 100 miles a week and want everyday to be a high intensity interval workout.”

“Too many people don’t run the slow runs slow enough that they aren’t able to do their hard runs hard enough. Without adequate stress and rest runners aren’t able to absorb the training that they are doing and then they can’t make the gains they are hoping to make.”

Durability and Recovery

“The easiest way to recover from a race is to be in shape for the race before you run the race.”

“There’s not a quick way to do it. You have to earn the fitness, the durability. And slowly, slowly build up.”

“It has nothing to do with effort. Emotionally you may be tough enough, but structurally you have to be tough enough otherwise you will break.”

Food, Diet, Nutrition, Weight and Supplementation

Tommy recognizes that everyone is different and our bodies are able to adapt to a lot of different fuel sources, but the best way he finds to describe his own diet is with the words of Michael Pollan from his book, In Defense of Food:

“Eat food, mostly plants. Not too much.”

“The more food I eat, the better I feel and the more energy I will have, but if I eat food and don’t burn it I will wear it. . . . If I don’t run over 100 miles a week I’m 180 lbs. If I don’t run enough miles, my body isn’t a runner’s body. It’s a farm kid’s body.”

“I find that learning to identify cravings has been really, really helpful. If I’m craving something sweet it’s that my body is craving carbohydrates. So I could eat a bag of Swedish Fish or I could eat bananas. And if I eat bananas, I will feel better. If I’m craving fat, I could go eat ribs, or I could add an avocado to my meal and if I eat the avocado I’ll feel better after. If I’m craving salt, I could eat a whole bag of potato chips or I could eat a pickle. Learning to listen to my body and what it’s telling me based on my cravings has been really helpful. Having an entire spectrum of options of things that will help me towards my goals and which things will hinder me is also helpful.”

“Another thing that helps me is to eliminate refined foods except during really intense training and racing.”

“I can get away with a lot of things that others can’t get away with because of how much I train.”

“The less meat I eat, the better I feel. But if I eat no meat then I have a really hard time regulating my energy. I would love to. I feel like the world would be better if we ate more plants and less meat. I’m more motivated to not consume any animal products because I don’t like the idea of killing animals more than any health benefits.”

“I kinda go back and forth depending on the time of year, what I eat. Depending on my cravings, depending on my training load.”

“I know a lot of people that are really, really strict with their diet and they run really fast and I know a bunch of dudes here [Flagstaff] who seemingly fuel off of beer and pizza and they’re the fastest people in the world.”

“Our bodies are incredibly, incredibly adaptable and they can take almost any combination of foods as long as everything that is needed is present and do incredible things with that. I think that just a reflection of how adaptable our bodies are and how unique our microbiomes are.”

Supplementation

Tommy shares the supplements that he takes:

- First Endurance Multi V

- First Optypgen HP – BetaAlanine, Rhodiola, Cordyceps

- Hemaplex (Iron + B Vitamins)

- Strontium (Increase bone density)

- Bone Up

- First Endurance Ultragen

Daily routine:

Wake up, get caffeinated and hydrated (sip some sort of hot caffeinated drink for a couple of hours while I read). Might drink simple electrolyte drink. “Recovery will be quicker if I don’t get dehydrated.” Eat bananas + walnuts. Run. Recovery shake with Ultragen, bananas, berries, peanut butter, etc. Half gallon.

“I eat almost completely plant based carbs for the first 8 hours of the day and then when I’m trying to “harden up” and get lean before a race, I eat almost exclusively animal protein after 4 pm until the next morning. So all carbs for the first 8 hours of the day and then no carbs for the next 16 hours.”

“There’s nothing magical about walnuts. I just like them.”

“I eat a lot of walnuts and a lot of bananas. 10 bananas a day and lots of rice and beans.”

Weight, Weight Loss, and Disordered Eating

“It’s typically easier to lose weight than to gain fitness.

“This is not as simple as the equation that fitness = amount of energy that you can put out / kg”

“The female endocrine system is very different than a male endocrine system.”

“I try not to let my mind to get too consumed by it. It’s not popular for males to talk about body dysmorphia and disordered eating, but it’s real. It’s definitely something that I’ve wrestled with for two decades. Sometimes its easier than other times.”

“I think because we grew up around wrestlers we didn’t ever view it as disordered eating. It’s not so much based off of trying to look the way that I think a normal male would want to look. It’s trying to look like the East Africans that I line up next to. It’s not healthy. It doesn’t look good. It’s not sustainable.”

“There’s a huge amount of pressure to run as fast as you can within the rules. It is a form of abuse if it is pushed upon you from another individual. But for me it has always been about fear of not reaching my potential. What could you do if you trimmed a couple more pounds off?”

“The hard part is that it’s physics. But what you’re not told in that simple one-dimensional physics equation are the other five dimensions that come into play: longevity, mental health, durability, bone density, confidence are the other things that you can struggle with for the rest of your life. For males it’s different than it is for females, but none of it is sustainable or something you would wish upon another person.”

“Take the stress out of it in any way that you can and do it because you love it.”

“I’ve been super fit and depressed and run terribly and I’ve been a little bit soft and stoked to be in it and run completely out of my mind. I’d rather be soft and happy than hard and sad.”

All of this and more in Episode 11 of the Art and Science of Running Podcast.

This episode is sponsored by ILO Endurance.

ILO Endurance is an online company dedicated to supporting the hydration and fuelling needs of endurance athletes. They deliver product fast, right to your front door saving you the hassle of going out to different stores!

They carry products like First Endurance, Gu, Endurance Tap, Clif, Picky Bars, and they’re one of the only retailers in Canada right now selling Generation UCan.

You get a 25% discount just for listening to this podcast…. use promo code ASR25 to claim your discount at checkout when you visit https://iloendurance.ca/

Intro and outro music GOIN 4 A WALK by Dallin Puzey.

Please listen, subscribe and rate this podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, YouTube, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Please follow us on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook and let us know what you’d like us to discuss in future episodes.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS | More